Air Fares & Probability Models

Explaining high-end domestic & short-haul fares

British Airways domestic fares can get so expensive that it is unrealistic anybody* will ever pay them. And while Qatar Airways is well-known for it’s good value fares, short-haul fares from Doha are sometimes not much cheaper than longhaul services.

* of course somebody will every now and then, but hardly ever, you know what I mean.

Here are some examples.

BA want GBP 1,834.60 (USD 2,436) for a Club Europe (biz-class) return trip from London to Edinburgh. The outbound is on Fri-16-May with an inbound on Wed-21-May. GBP 1,770 of this is the fare that BA receive. GBP 64.60 goes to airports and HM Treasury.

The rail operator on the route charges no more than GBP 654.60 for a First Class return ticket.

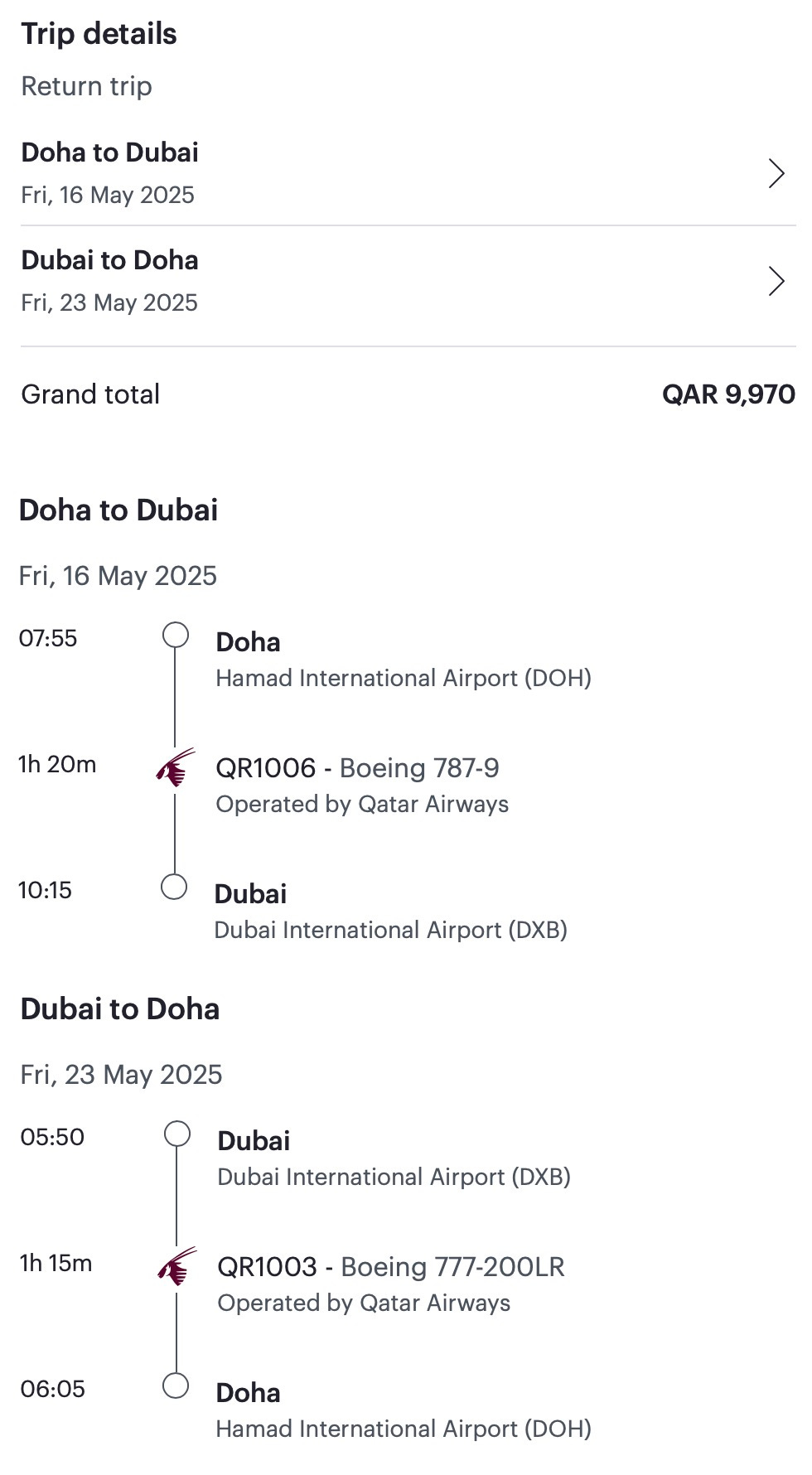

Qatar Airways has similar issues. For this trip from Doha to Dubai they want QAR 9,970 (GBP 2,061) in First Class.

BA is over a thousand Pounds more expensive than the rail equivalent. Qatar Airways is charging more than a thousand Pounds for an extremely short flight.

Revenue Management 101 would state that the airline charges these fares because that is what the market allows and that is what people are willing to pay. This is not actually correct.

In fact we have a corner solution (see article). These airlines are pricing this way because they do not actually want people to buy those tickets.

Now let’s see why that is the case…

When airlines measure how profitable their flights are, the calculation is not clear-cut. They are reasonably sure about what it costs – fuel burn, crew costs, insurance, depreciation, handing over taxes to the treasury and so on. The problem is allocating revenue.

When a passenger buys a simple single or return ticket things are easy. For one-way tickets all the revenue goes to the flight in question. For returns, even open jaws, ticket value is split in accordance with the fare calculation.

For readers unfamiliar with fare calculations, try pricing up an itinerary on ITA Matrix. You will see it there at the end of the process.

So even when a passenger has been booked into different fare classes on different parts of their journey, allocating the revenue is easy.

But many passengers are taking connecting flights. Pricing is often origin-destination based rather than flight-by-flight. This means that one number in the fare calculation needs to be divided between two or more flights.

So airlines measure a flight’s revenue contribution in two ways:

1. Revenue at the flight level: all the revenue is divided between flights based on the proportion of miles that each flights represents of the total. For example, a 500 mile flight followed by a 1,000 mile flight would see one third of the revenue allocated to the first and two thirds to the second.

2. Revenue at the network level: all of the revenue from every ticket is allocated to each flight on the ticket.

There is also a route level where all the flights on a multi-frequency route are added together.

The sum of flight level revenue equals total network revenue. The sum of network level revenue exceeds total network revenue.

Performing the same analysis for profitability looks the same. The sum of flight level profitability equals total network profitability. The sum of network level profitability exceeds total network profitability.

Understanding the different perspectives between the flight level and the network level explains why BA’s Edinburgh fare and Qatar Airways’ Dubai fare are so expensive.

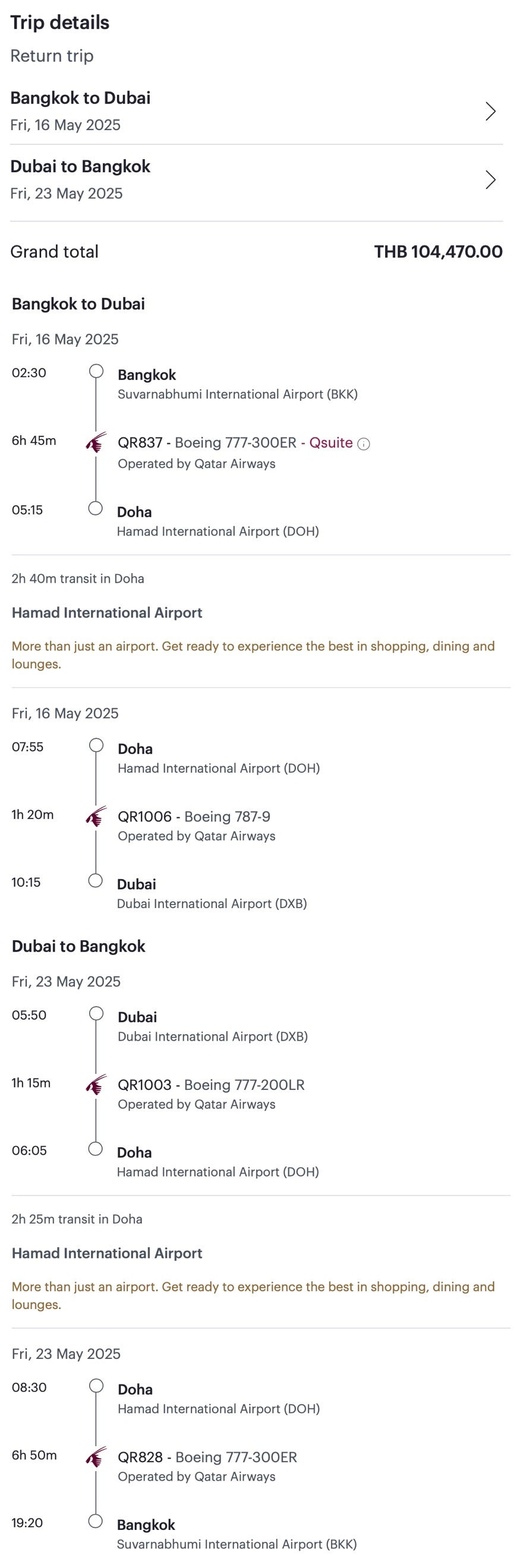

Take a Qatar Airways itinerary from Bangkok to Dubai that uses the same flights that I showed in the example above.

Qatar Airways want THB 104,470 (QAR 11,648, GBP 2,399) for this return trip in Business Class.

Selling a regional First Class seat from Doha to Dubai and back might mean that Qatar Airways is unable to sell a longhaul Business Class seat from Bangkok to Doha and back.

It looks to me like Qatar Airways believe they are almost certain to sell longhaul Business Class seat on the back of their shorthaul flights to and from Dubai.

They get QAR 11,648 less a few airport charges for the Bangkok to Dubai itinerary and QAR 9,970 for the Doha to Dubai itinerary.

Think about this in probability terms.

9,970 / 11,648 = 85.6%.

There is roughly an 85.6% chance that selling a ticket on Doha to Dubai and back will displace a passenger on Bangkok to Dubai and back, or another similar itinerary. This must be so, otherwise the Doha <> Dubai fare would be lower.

The shorthaul fare is set to ensure that if a shorthaul sale is made, it is enough to cover the risk of not selling a seat to the longhaul network.

Now let’s turn back to BA’s GBP 1,770 fare to Edinburgh. I do not see this as a real air fare anymore. Realistically nobody in the UK is actually going to pay this fare.

I see it as representing a 50% chance that they will sell a pair of longhaul seats to an Edinburgh passenger for GBP 3,540.

Or a 25% chance that Edinburgh will feed GBP 7,080 to or from the longhaul network.

Viewing some types of shorthaul airline pricing as a form of probability modelling to cover the risk of displacing longhaul seat sales can help explain outwardly bizarre airline behaviour.

Tales from the road – a fare rule workaround that “solves” the problem above

Out on a project somewhere in the European Union, your favourite airline revenue economist had a choice of two BA flights.

One left at zero dark hundred hours and was £200. The other with a much more convenient mid afternoon departure and a nice slice of Battenburg cake was > £1k.

I am not known for my love of early starts, but waking a few hours early to save £800+, even on the company dime, seems sensible to me.

Fortunately I got to save the money and take a lie in with a slice of Battenburg for later.

The Club Europe fare rules permit a free of charge same day change provided that:

1. The airports are the same

2. The change is made on the day

3. There must be seats available in Club Europe on the new flight, in any fare class.

So at midnight I logged on to the BA app and changed my flight to the more expensive afternoon option with the cake. I even got seat 1A!

This BA Club Europe fare rule is a most handy workaround that every European traveller should be aware of. It makes sense for BA because by the time that the clock strikes midnight (almost) all of the longhaul bookings have been made. So there is no displacement cost.

Everybody wins. BA wins because they get the chance to maximise sales on their pricey longhaul network. Longhaul passengers win because they get better access to seats. Shorthaul passengers win when there is a seat left at the end of the day.

Next week, Eurovision…

Get ready to wave your national flags, Eurovision is coming! And as is traditional here on Airline Revenue Economics, I will be investigating who are the main airlines feeding fans into the annual jamboree of whacky performances and sparkly costumes. Read last year’s airlines of Eurovision article here!!

Read more about British Airways and Qatar Airways on Airline Revenue Economics

Why is Flying To & From Doha so Expensive?

All Change in Categories 16, 31 & 33 at BA

BA's new Head of Revenue Delivery

Qatar Airways's caviar strategy: a deep dive

BA's Advance Booking Curve Revealed

Three pitfalls for Qatar Airways to avoid

Costing BA's Avios-only flights to Dubai