Battle of the Beds: Club World vs Upper Class

The average passenger sleeps for slightly longer on BA due to network design

The fully-flat bed is one of the greatest innovations in aviation. Helping people get a good night’s sleep when crossing continents helps travellers buy time to close deals, enjoy holidays and make the most of their trip.

But how much sleep do they generate? My model suggests just under three hours per passenger. In this article I am going to use my model of airline schedule data and some assumptions about how people sleep on flights to find out.

This article was written using data from OAG Schedules Analyser: visit oag.com. Thanks OAG!

Today two great business class cabins from London-based British Airways (BA) and Virgin Atlantic will be playing against each other. I last ran this analysis in early 2023 (see article). Let’s see what has changed.

Who will be the winner? Read on…

Why are flat beds and sleep relevant to airline revenue?

Fully-flat beds are great revenue generators. People know that a flat bed will help them sleep. As a result they may be more likely to travel or desire upgrades to business class, boosting demand. They may also be willing to pay more for the experience.

The concept is highly marketable, thanks to a desirable product that is easy to explain and simple for anyone to understand.

These snazzy seats have generated far more revenue than NDC-powered offer-order retailing (see article), an industry programme to help airlines package travel products together. Their value proposition in Business Class is so compelling that airlines have forgotten how to sell First Class (see article).

On a typical flight to Dubai, which is operated by both BA and Virgin Atlantic, I estimate that Business Class generates around 47.5% to 48.4% of total revenue (see article).

The history of flat beds

Beds on planes have been around since the early days of mass market aviation. In Martin Scorsese’s film The Aviator, TWA founder Howard Hughes played by Leonardo di Caprio asks Pan Am’s boss Juan Trippe about choosing zippers or buttons for the curtains across passenger bunks at some time in the 1930s.

But beds that turn into seats are relatively new. London-based British Airways (BA) was the first to introduce the idea in the mid-90s. They kitted out their 747s and 777s with 14 or in some cases 17 pods (see article), supported by demand from corporate contracts specifying First Class for top execs.

Flat beds came to Business Class at the turn of the millennium with New Club World, BA’s game-changing business class. BA’s Club concept had always promised to deliver the business man ready to do business. With flat beds it was able to do so even better than ever before.

BA had to do a good job. Groovy-funky Virgin Atlantic (see article) play hard at Heathrow. They once put demo Upper Class seats outside the BA lounge pavilion at Heathrow Terminal 4. Guerrilla marketing, airline style.

Despite a considerably smaller network (BA have 7.6 times as many seats a week than Virgin), Virgin Atlantic has tremendous brand recognition. I think it is fair to say that Virgin Atlantic’s Upper Class is a flying nightclub to Club World’s flying office.

Club World is now on it’s third generation bed and fifth generation seat overall. The pictures below show how the cabin has evolved through the years.

My personal favourite is version 2, which was extremely comfy. The current Club Suite has more space and storage but suffers from a cramped and inflexible foot rest.

Upper Class is currently available in three versions. The Upper Class 787 seat is close to the original Suite from around 2004. Many think it outdated. I found it fine.

Other European and Transatlantic airlines would never have invented the fully-flat bed because there was little commercial imperative.

Even today Lufthansa’s over-complicated Allegris Business Class is a confused jumble (see article). Allegris First Class confuses features and benefits (see article) and seems destined to eventually kill the front cabin for Lufty and Swiss.

So which of Club World and Upper Class generates the most sleep? Read on…

What is an overnight flight?

I took a week of schedule data for this week, Sun-8-Jun-2025 to Sat-14-Jun-2025. This is the equivalent week in the calendar to when I last looked at this in early 2023. So we can compare the results.

I defined a night flight as one that arrives at it’s destination after 4am the next day or departs before 4am on the same day that it arrives.

These examples are “obviously” night flights. They leave late and arrive early.

BA106 0105 DXB LHR 0550

VS138 2325 JFK LHR 1125+1

Some others are a little more ambiguous…

BA52 1330 SEA LHR 0650+1

BA282 1540 LAX LHR 1005+1

BA169 1210 LHR PVG 0755+1

VS92 1610 MCO LHR 0550+1

BA282 from LAX is perfectly timed for sleep if you only arrived a day or two ago from Europe and are now heading back. The 1540 departure is 2340 in London. It is also perfectly timed to do some work, have a meal and watch a movie before resting in your hotel the next day if you are on California time.

I took BA169 to Shanghai and the now terminated but similarly timed BA17 to Seoul in 2019 in First and Club World respectively. BA offered a breakfast service as the second meal on both flights but as far as I could see hardly anyone slept.

On flights like these people will sleep. It may even be the case that most passengers will sleep some of the time, as boredom and flying go hand-in-hand. But some flights will have lots of people sleeping and other will not.

How focused on night flights are BA and Virgin Atlantic networks?

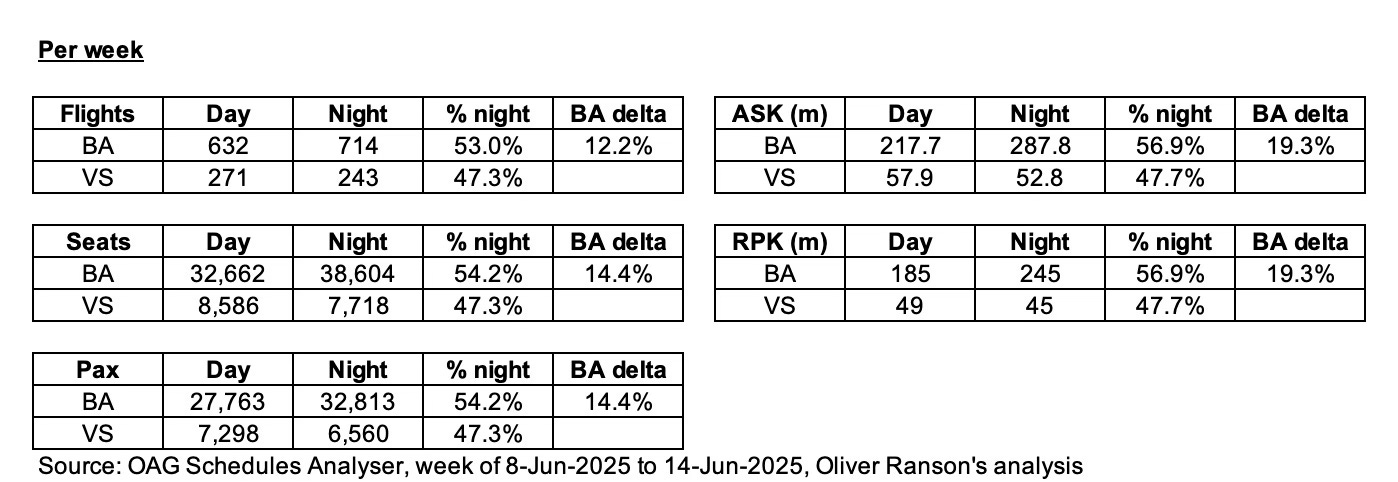

The table below shows that BA’s network seems to be more calibrated for night flights than Virgin Atlantic’s and so sleep may be more important to the average Club passenger than Upper Class traveller.

Overnight flights are supposedly more attractive to business travellers, who “waste” less time. This may be less relevant in the age of on-board wi-fi.

Overnighters may also encourage people to buy-up to business class. This increases demand and willingness to pay, and so revenue, for the higher cabin.

If this is a conscious decision by BA it is a smart move. I would wager that it was indeed a smart move by somebody. But I would also wager that this decision was made a long time ago and the knowledge has been long forgotten within the airline.

Our of the total number of services, BA has 12.2% more night services proportionally than Virgin Atlantic and 5.7% more in absolute terms. This is up slightly from 2023, when the numbers were 4.5% (proportional) and 2.2% (absolute).

The same is true for seats and passengers, assuming an 85% seat factor. It is even more pronounced for ASKs and RPKs. This is partly because some of BA’s longest flights, such as Hong Kong and Singapore to Sydney, are all overnighters and much longer than anything Virgin Atlantic has to offer.

Perhaps Upper Class is not so much of a flying night club after all.

Modelling how people sleep on planes

I am not aware of any public data about how people sleep on planes. Some airlines and seat manufacturers will surely have done research, but I have not seen it. Please send a postcard if you know of any.

So to understand which of Club World and Upper Class deliver the most sleep I am delving into the realm of “reasonable assumptions”!

A lunchtime flight from London to Shanghai might well arrive in the morning, but not many people on UK time will be getting a full night’s sleep. On some of BA’s monster flights like Singapore, which are not served by Virgin Atlantic, even a passenger sleeping all through a full night will not be asleep all the way.

Meanwhile It is not uncommon to get a few hours of shut eye on a westbound trans-Atlantic flight operating entirely in the hours of daylight.

The data point I have is Air New Zealand in Aircraft Interiors Magazine. They said that their research showed that people start to wake up after four hours. That makes sense – planes are loud and unfamiliar, to make staying asleep taxing. Of course during the day, most people napping will sleep for an hour or two or three. But overnight I stick with the four hours plus idea.

So here is my table of “reasonable assumptions”.

The % of pax asleep column is never zero because there are always some people on a different time zone.

The wake rate per hour of sleep shows the number of people who I assume will wake up once they have had a certain amount of sleep, if the flight is long enough. On clearly overnight flights only a few people wake up before Air New Zealand’s four hours. On day flights I imagine that people will tend to sleep for only a few hours.

Some people take sleeping pills to get more than a full night’s sleep. But I limit sleep to ten hours. The model forces people to wake at 20 minutes to landing.

It also does not include sleep before the seat belt sign is turned off because the seats are not in fully-flat bed mode at that time.

The results!

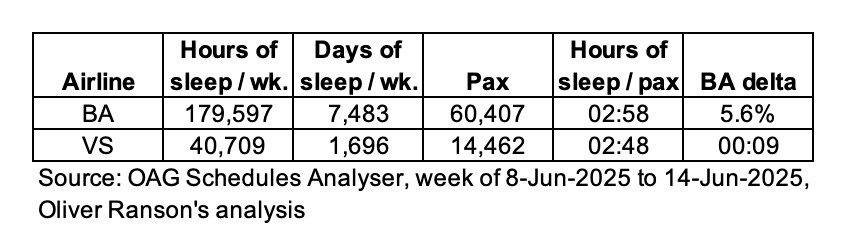

Based on these parameters the average Club passenger will sleep nine minutes longer than an Upper Class traveller. This is slightly longer than in 2003, when BA Club delivered seven minutes more sleep on average.

Together the two airlines deliver an impressive 9,179 days of sleep a week.

But although BA delivers more sleep overall, Virgin passengers spend a longer portion of the flight asleep. I totalled up the total number of passenger flying hours and the total number of hours that passengers spend asleep. The ratio between them, the “Sleep Factor” if you like, is 37.6% on Virgin Atlantic and a slightly lower 36.7% of BA.

Zzzzz…!

Conclusion

Airline fully-flat beds generate just under three hours of sleep per passenger, according to my analysis of BA Club World and Virgin Atlantic Upper Class. Which airline delivers the most sleep?

BA passengers get about nine minutes more sleep on average due to longer stage lengths. But the average “Sleep Factor”, the portion of the flight spent asleep, is slightly higher on Virgin Atlantic (37.6%) than BA (36.7%).

So I declare the “Battle of the Beds” a tie!

Why does this matter?

Fully-flat beds are great revenue generators. Perhaps the greatest product marketing in all of aviation.

People know that a flat bed will help them sleep. As a result they may be more likely to travel or desire upgrades to business class, boosting demand. They may also be willing to pay more for the experience.

The concept is highly marketable, thanks to a desirable product that is easy to explain and simple for anyone to understand.

These snazzy seats have generated far more revenue than NDC-powered offer-order retailing, an industry programme to help airlines package travel products together. Their value proposition in Business Class is so compelling that airlines have forgotten how to sell First Class.

On a typical flight to Dubai, which is operated by both BA and Virgin Atlantic, I estimate that Business Class generates around 47.5% to 48.4% of total revenue.

Airline fully-flat beds generate just under three hours of sleep per passenger, according to my analysis of BA Club World and Virgin Atlantic Upper Class. Which airline delivers the most sleep?

BA passengers get about nine minutes more sleep on average due to longer stage lengths. But the average “Sleep Factor”, the portion of the flight spent asleep, is slightly higher on Virgin Atlantic (37.6%) than BA (36.7%).

Airline should continue to invest in fully-flat beds. But I doubt we will see much innovation in Europe anymore, unlike when BA and Virgin Atlantic pioneered the yin-yang and herringbone configurations.

Innovation requires a commercial imperative. Lufthansa’s Allegris is a confused jumble. United’s Polaris is a mess. Qatar Airways’ Qsuite however was a great success (see article). Cathay Pacific’s Aria looks beautiful.

I look forward to seeing and hopefully sleeping in many more lovely flying flat beds in the future.

Read more on Airline Revenue Economics

BA's new Head of Revenue Delivery